It’s pretty well known that Ohio had many stops on the Underground Railroad or UGR (which did not consist of an actual train running through a tunnel). Both before and after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, some residents believed that slavery was morally wrong and helped escaped enslaved people get across Lake Erie and into the freedom of Canada.

There are some big names in the history of abolition in the state, like John Brown, John Rankin, and Harriet Beecher Stowe. As far as locations, or stops, on the UGR, they go from the south end of the state, like those in New Richmond all of the way to Cleveland and other cities on the Lake Erie coast. With so many stops and such a glowing history, it’s easy to think that everyone in the state pre-Civil War were in favor of abolition. The truth is much less happy, as seen in the case of Hiram Miller.

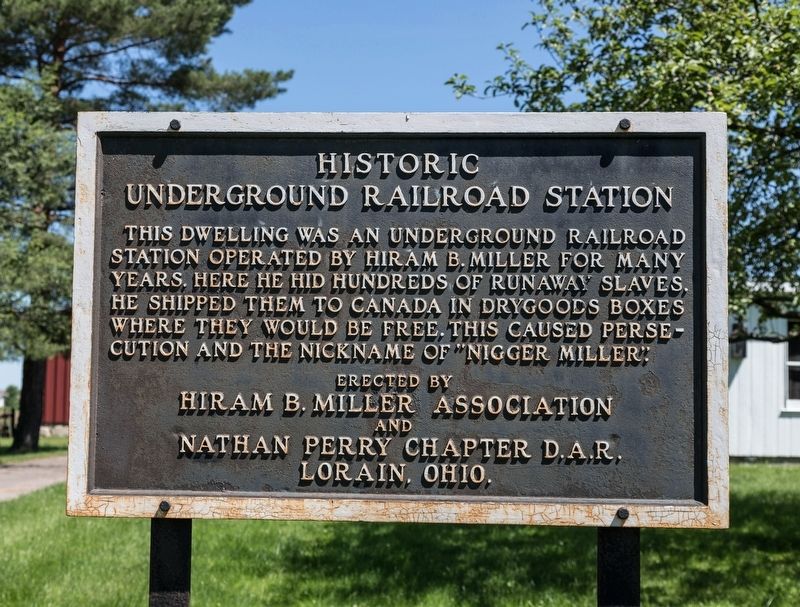

Hinckley Abolitionist Hiram Miller

Born in New York state in 1807, Hiram Miller moved with his family to Hinckley in 1833. Even at this point, he was an ardent abolitionist, determined to do his part to help escaped slaves make it to freedom. His farm, located at the corner of West 130th and Laurel, was known as a safe space. Miller would hide people in his barn or in his mill and help them hide in the back of a wagon covered by hay. Someone else would then drive the wagon to stops further north, like Dover Bay (now Bay Village) where the escapees would get on a boat bound for Canada and away from the Fugitive Slave Laws.

Because of this, as well as his rather outspoken views on abolition, some of Miller’s neighbors hated him. They threw rotten eggs at him, drove him out of churches, and even forced him to ride on a rail (a punishment that involved attaching him on a fence rail held up at either end by two or more people, parading him through town to be made fun of, and then dumped on the ground at city limits.)

The neighbors kept an eye out for escaped slaves on his property so that they could “call in” the slave catchers, although this never panned out and none were ever caught on Miller’s farm. At one point, Miller’s neighbor physically assaulted him, grabbed him by the throat and threw him on the ground so hard that he wound up with a bloody head wound.

Although Miller had some supporters, including his wife, there were plenty of detractors. In an illustration of the mixed sentiment at the time, a picture of President Abraham Lincoln was hung in the back of a church. Parishioners broke into the church one night, ripped the photo off the wall, and stomped the glass cover into powder.

Helping Thousands of People to Freedom

Hiram Miller not only reportedly helped a thousand (some sources say 3,000) or so people reach safety, but he also employed freed black people on his farm. He truly believed in the “all men are created equal” clause in the Declaration of Independence. However, it’s questionable whether he brought a black friend to his all-white church for because he thought they were equal and the friend belonged, or if he wanted to antagonize the members of the church, or both. Either way, on this particular occasion he was seated in the least desirable spot, right in front of the open heating stove, and eventually thrown out of the church in the middle of the sermon.

Despite the fact that Miller’s neighbors called him “N-word” Miller, he went around and spoke about abolition in schools, teaching kids that slavery should be banned. He even wrote songs about the topic and sang them loudly in church when there was a lull in the service.

Hiram Miller died in 1888, having helped thousands of people escape from slavery in the south. He’s buried in Town Line Cemetery in Brunswick, Ohio.