Cleveland, Ohio

Erie Street Cemetery is located in downtown Cleveland, sandwiched between East Ninth and East 14th Streets, as well as Erie Court and Sumner Avenue. Even though the cemetery takes up more than a few blocks, it’s easy to overlook, thanks to its proximity to other attractions, like the Guardians’ Progressive Stadium, Gray’s Armory, and, to the north, Playhouse Square. With that said, the cemetery is worth wandering through.

Not only is Erie Street Cemetery the first still-existing burial ground in Cleveland (Ontario Street Cemetery was technically the oldest), but it also holds the graves of many important people who played a role in the early years of the city.

The History of Cleveland’s Erie Street Cemetery

The first burials took place in Erie Street Cemetery (the moniker comes from the old name for East Ninth Street) in 1826. Many of the notable graves are close to the East Ninth St entrance, including those of the first permanent white settlers in Cleveland, Lorenzo and Rebecca Carter, who arrived in the area in 1797.

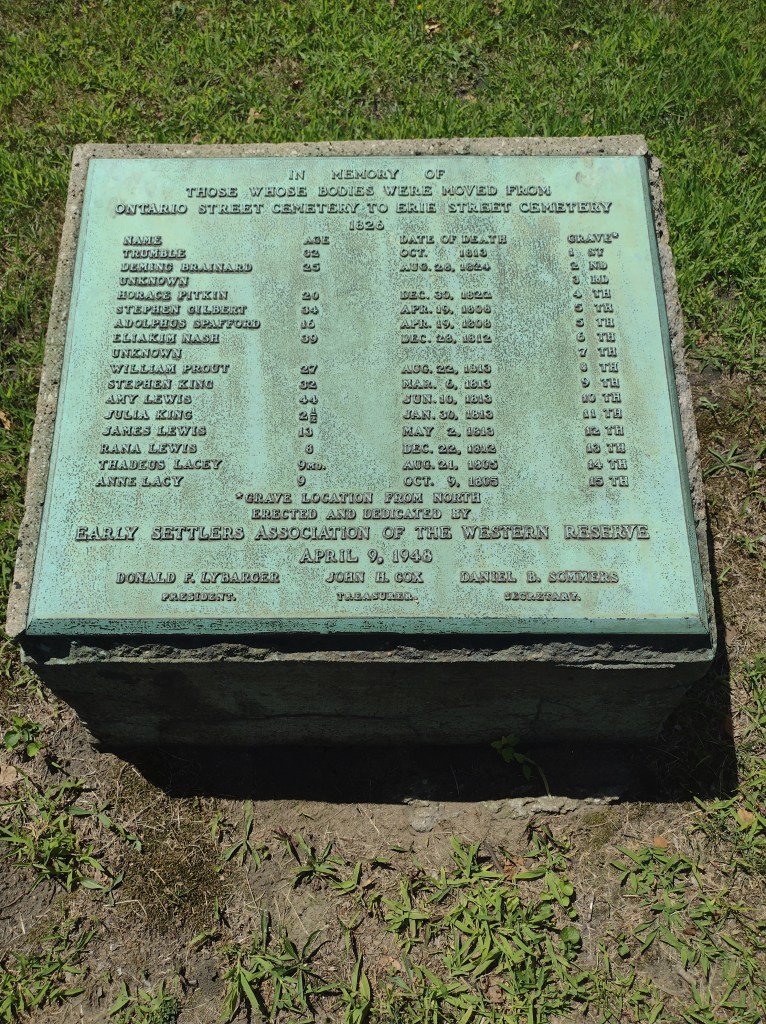

Nearby their memorial is one for the bodies removed from Ontario Street Cemetery, located roughly where the JACK Casino parking garage currently sits. They include the first person to die in Cleveland, David Eldridge, who drowned in 1797. His body, as well as several others, was moved to Erie Street Cemetery in order to make room for Prospect Avenue back in the 1830s. Others from that cemetery wound up in Lake View Cemetery or Harvard Grove Cemetery.

Some of their headstones were moved, too:

Other Interesting “Residents” of Erie Street Cemetery

There are two prominent Native Americans buried in the cemetery. One is Joc-O-Sot, a Mesquakie chief who wound up in Cleveland after the Black Hawk War. In the 1830s, he befriended Dr. Horace Ackley, a well-known surgeon. Joc-O-Sot, also known as Walking Bear, met Dan Marble through Dr. Ackley.

Marble ran a theater group and needed a Native American actor, so Joc-O-Sot joined them and toured the world until he died, possibly of tuberculosis, in 1844. Rumor has it that his body isn’t actually in his grave, as it was stolen by thieves and sold to medical schools for experimentation purposes. His ghost supposedly walks around the cemetery at night.

The other, Chief Thunderwater (born Oghema Niagara) was related to the Sauk/Ojibwe tribe through his father and the Seneca tribe through his mother. He spent time helping promote the works of his fellow Native Americans, was a well-known activist for Native American rights, and even traveled the country as a part of Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show.

Chief Thunderwater settled in Cleveland after retiring from showbiz and opened Preservative Cleaner Co., which made polishes, teas, and herbal remedies. He died in 1950 and is buried near Joc-O-Sot.

War Veterans in Erie Street Cemetery

There are also numerous Revolutionary War, War of 1812, and Civil War veterans buried in the cemetery, including Jabez W. Fitch, a Civil War soldier who ran Camp Taylor before retiring from service and setting up a Cleveland real estate firm. Another is Civil War General James Barnett, who played a role in the construction of the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument and worked as a President for several local banks.

Controversies Over the Years

Of course, nothing, not even a cemetery, is without controversy, especially one located on prime land in the middle of downtown Cleveland. The first occurred in the 1830s, not long after the cemetery opened. The land that it’s built on was sold to the city by Leonard Case, Sr for $1. Deciding that there was “extra land” to use, Cleveland let businesses use a portion of it for a gunpowder magazine and a poorhouse.

Case’s heirs unsuccessfully sued the city over this additional usage.

Another issue stemmed from the Jewish population of Cleveland. At the time, due to a lack of cemeteries in the area, Christians of multiple denominations used it to bury their dead. The Jewish people in Cleveland wanted to be able to use the cemetery as well, but their petition didn’t go through, leaving them to found Willett Street Cemetery instead.

Finally, throughout the early part of the 20th century, city leaders and developers wanted to carve off parts of the cemetery for streets and other uses, moving the bodies to nearby Lake View or Highland Park Cemeteries. Thankfully, the Pioneers’ Memorial Association, formed in 1915 to oversee the cemetery, managed to fight back, and the space will remain what it is today.

Sources

- Encyclopedia of Cleveland History: Joc-O-Sot or Walking Bear

- The Skeleton Key: The Mystery of Joc-O-Sots Bones

- Encyclopedia of Cleveland History: Chief Thunderwater

- Find a Grave: Erie Street Cemetery

- Rose, William Ganson. Cleveland: The Making of a City.

- Encyclopedia of Cleveland History: Jabez Fitch

- Encyclopedia of Cleveland History: James Barnett

- Cleveland Historical: Erie Street Cemetery

- Encyclopedia of Cleveland History: Erie Street Cemetery